Programme Management

All organisations have to change, so an ability to “make things happen” is important. Z/Yen treats the effective and efficient management of programmes and projects as a key skill. Not only do we provide programme and project management for clients, we have to manage our own portfolio of projects. We set out below the background to programme management and some of the tools and approaches that Z/Yen finds helpful. Programme management is the co-ordination of a portfolio of projects in order to achieve a set of business objectives.

Organisations need programme management in order to handle either a multitude of projects or a mega-project that initiates a plethora of sub-projects. Programme management involves the planning, prioritisation, monitoring, support and evaluation of projects to meet changing business needs. The objective of programme management is to increase the likelihood of success within the project portfolio and, through co-ordination, increase the overall impact of the portfolio on business objectives. Programme management complements project management, but it differs from project management in that programmes tend to have a set of objectives rather than a single objective, be at a larger scale of complexity, involve heterogeneous projects and require cross-project resource sharing.

A computer-based entertainment company found that many of its projects were late, over-budget and failed to achieve what had been expected. Further, some of their larger client relationships were under strain even when several projects had been successfully delivered because one or two key projects had failed. They realised that they were: spreading resources too thin by trying to do too many projects; confused about how decisions were made on starting, stopping or changing projects and who was responsible for making these decisions; failing to coordinate design changes or new timetables with clients and customers; unsure how resources were allocated; often losing track of good ideas, especially ideas that might benefit several projects; failing to learn from either success or failure. The solution to these problems was a significant project in its own right – putting in place a programme management system along with a financial project evaluation system and training and development for their project managers and staff. The programme management system was designed by the project managers themselves both to ensure that it reflected their needs and to give them a sense of ownership. It was ‘their’ system. Built into the system was a strong bias to be ‘customer driven’; customer needs came first. After the programme management system was designed, the company appointed a programme management ‘czar’ with the power to start and stop projects, as well as the responsibility for monitoring and support. Naturally, there were some manuals, some structured training and plenty of discussion, but ultimately the company began to see the benefits: a clear view of the totality of projects in the organisation, their likelihood of meeting objectives, their resource consumption and their key risks; projects likely to fail were cancelled, releasing resources to other projects and increasing overall success; cross-project problems were getting solved, e.g. a piece of software that was causing all projects problems was replaced using a quick, mini-project; clients gained more confidence in overall delivery because projects were more consistently run and they had more information during the course of projects across projects.

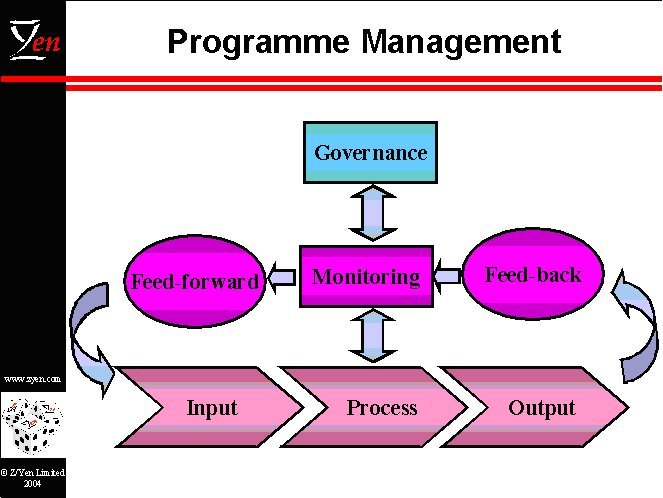

Programme management, as with any system, has five basic components:

- Governance: setting out the overall objectives of the business, planning a set of projects to achieve those objectives and having clarity on go/no-go decisions;

- Input: selecting specific projects to undertake, gaining stakeholder commitment, assembling resources and appointing a team;

- Process: supporting the project managers through cross-project discussion, training, template materials and methodologies;

- Output: evaluating projects, focused on a ‘customer’ point-of-view, so that people learn from both successes and failures;

- Monitoring: providing management information up to governors, over to customers, down to project managers and across project managers so that they are co-ordinated. Monitoring also uses feed-back from project outcomes to feed-forward into new projects and re-plan the shape of the project portfolio.

Programme management can be represented diagrammatically as:

There are a number of tools that can be used in each component, but some of the more interesting tools include:

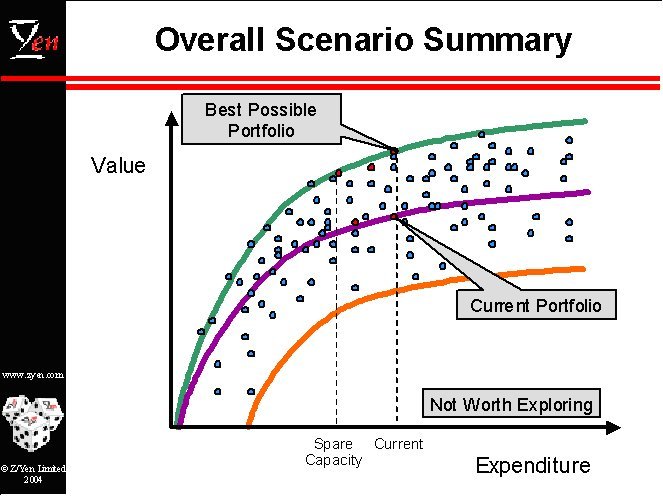

Governance – Portfolio Analysis

Programme management starts with a strategic review of the organisation and its objectives. However, as stated at the beginning, programme management is at a larger scale of complexity than project management, so how can a more optimal set of projects be selected? Using portfolio analysis to select projects is a common, useful tool. Portfolio analysis is a well-established practice in the commercial sector, e.g. financial services or pharmaceuticals, and involves balancing a portfolio of investments in a way which limits risk (by managing volatility) and maximises potential rewards. Companies and not-for-profit organisations adopt a similar technique in selecting ‘investments’ - activities in which they are involved. A simple portfolio analysis can be carried out as a paper based exercise, while larger, more complex organisations may need to use statistical modelling techniques such as Monte Carlo analysis. Portfolio analysis helps organisations challenge established thinking by providing a set of plausible but unconsidered options to generate debate and better, informed decisions.

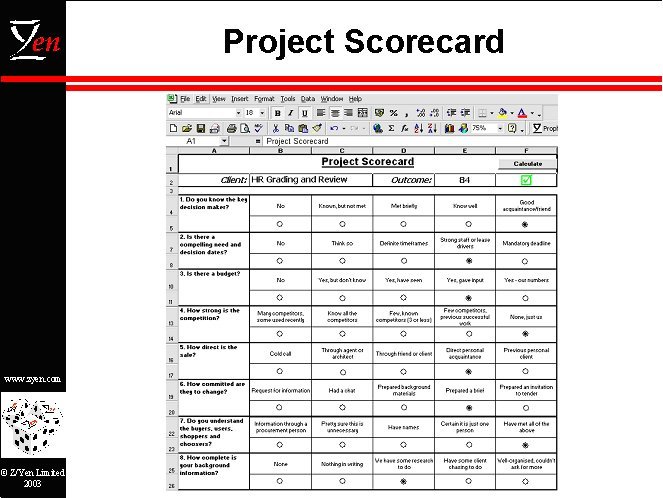

Input – Project Scorecards

The outcome of governance is a set of ‘themes’ or overall goals for the organisation and these lead to specific project selection. This is the evaluation and selection of projects that are aligned with the overall goals, and frequently linked in complex ways, e.g. we can’t get into Far Eastern markets until we establish our Singapore office. The programme management team need to ask some basic questions before approving a project:

- Is this project a good idea?

- Will this project help the organisation and its stakeholders?

- Is there a clear customer who gets a clear benefit, perhaps that they are willing to share?

- Is this of acceptable risk to the organisation?

- Does this advance the mission of the organisation and have a return-on-investment?

- Do we have consensus and agreement about this, including agreement outside the organisation?

- Have we researched this idea to an acceptable level?

- Have we prepared a business case, quantification of timescales, milestones, costs, benefits and risks?

- Who in the organisation is most suitable to run this project?

A sample scorecard is illustrated above. The idea is to approve projects over a certain score. However, projects that fail the ‘hurdle’ can re-adjust to try again. Ideally, the scorecard becomes more statistical over time, reflecting what the organisation learns, e.g. projects with many clients are too risky for us most of the time.

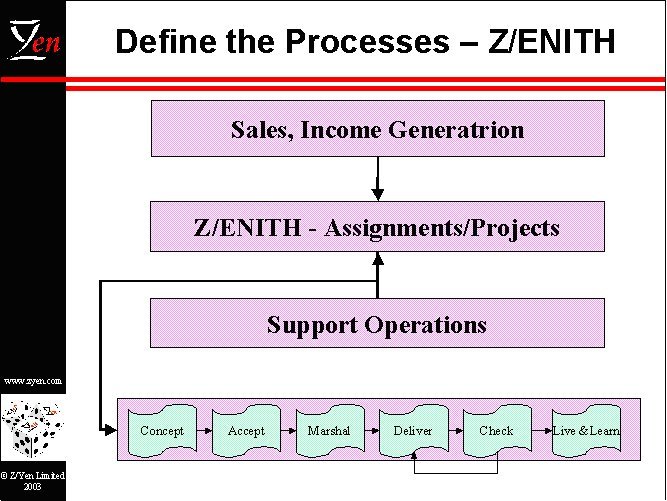

Process – Project Support Office (PSO) and Z/ENITH

Typically, an organisation concerned with “programme” management, by implication, is likely to benefit by establishing a project support office that increases the effectiveness of the multitude of projects. For instance, at one client, projects were very late, substantially over budget and not satisfying ‘target users’. Following a review, Z/Yen recommended forming a Project Support Office (PSO) headed by a Programme Manager. In discussion with the client, Z/Yen also recommended the use of interim skills to get the PSO up and running. Z/Yen’s first Programme Manager worked over six months to set out the PSO’s policies, procedures, methodology, reporting, staffing and training. He drew on extensive formal project management and business process development skills, e.g. PRINCE. Moreover, he changed the bias from ‘target users’ to customers. As the post was new, Z/Yen convinced the client that the first Programme Manager, who set up the PSO, should be followed by a second, ‘hardened’, interim Programme Manager before seeking a full-time person. Z/Yen’s second Programme Manager succeeded in transforming the client’s culture from operationally-based to project-based over the following 12 months. With a successful PSO running well, and a much better idea of the personality requirements, the client was able to specify the requirement for a full-time person more accurately and show candidates the appeal of the position. By this time, the chosen candidate came from within the organisation. She had learned enough from the previous two Programme Managers to take on the position and continue further her professional development in project and programme management.

Structured programme management needs structured project management. There are many potential sources for structuring project management ranging from very thorough, e.g. PRINCE, to a simple control spreadsheet. An important decision is to choose an appropriate level of management for the scale of programmes. Within an organisation, programmes and projects can be of varying sizes; the trick for successful programme management is to have a flexible suite of tools that enable consistency with scalability. Typically, at a high-level, a six-stage process of one-page checklists is sufficient. A good example is Z/ENITH:

- ‘Concept’ is a formalised approach to project definition. It tries to take good ideas and get them into shape for proper consideration. Ideas become project proposals signed off to proceed to consideration;

- ‘Accept’ involves project acceptance and sign-off, e.g. using scorecarding. It allows organisations to define where responsibility for projects lies, at what level decisions are made and who has ultimate responsibility for resources and costs and whether to proceed at all;

- ‘Marshal’ concerns the management of resources and timeframes. As well as assembling teams and budgets, marshalling introduces checks and controls such as work plans, project calendars, staff commitments, progress reports and key stage meetings;

- ‘Deliver’ is the stage at which the work gets done. During delivery, plans are reviewed, progress reports are issued, relevant documentation is prepared and distributed, cost and resource estimates are reviewed and updated and any problems are identified and resolved;

- ‘Check’ provides a framework for checkpoints and milestones, for deliverables to be accepted, costings to be signed off or appraisals and coaching to be performed;

- ‘Live & Learn’ is a formalised approach to project evaluation, including the final acceptance, review of the project, debriefing, ensuring that value has been obtained and lessons learned. One of the crucial questions is not whether the project delivered, but whether the benefits were realised and the results of the project handed over successfully to the clients.

Output – Project Appraisal

Just as people should be appraised at the end of major assignments or periods, so should projects. A formal appraisal process is crucial to organisational learning. Successes and failures of the project are evaluated and recorded so that learning can benefit future projects and the people involved in future projects. Questions asked at this stage include:

- What did we learn?

- Was the project delivered on time and if not what can we do to prevent future over-runs?

- Was the project delivered within budget and if not how can we prevent future overspend?

- Did the project achieve its objectives?

- Have we critically assessed any complaints?

- Have we identified materials and processes that may be relevant or reusable for other opportunities?

- Are there any further projects that lead naturally from this or enhance the results of this?

Organisations are different and require different processes. Tools can be adapted and added additional tools applied, for example problem-solving methodologies, to a variety of different cultures and organisations.

Monitoring – Management Information

Monitoring systems are a rich topic, but the key thing is to recognise that projects are about the future rather than the past. The implication for monitoring is that management information needs to be able to handle a range of outcomes, e.g. bottom, expected and top, rather than just a single point of information, typical of historic information in financial systems. There will be a range of reports that give management confidence, for instance:

- Project summary data showing dates, costs, people, benefits, time variations, budget variations, scope variations, expected returns;

- Expected return on programme portfolio;

- Breakdowns of resource usage, utilisation, staffing gaps, milestones, risk areas.

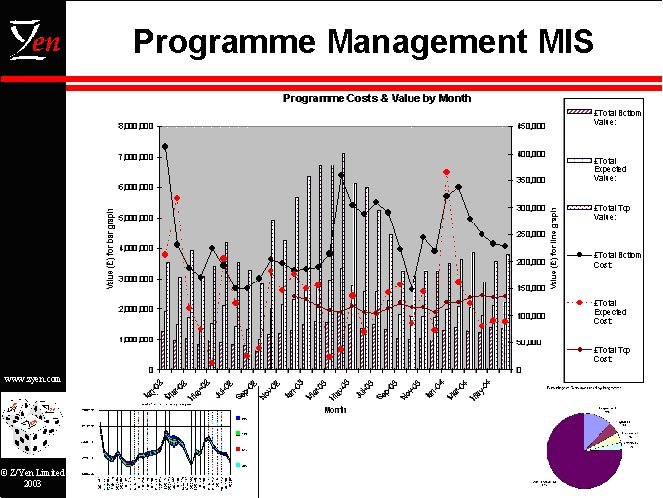

For instance, a well-managed programme management unit should regularly, i.e. weekly or monthly, be able to produce graphs such as the following showing the overall state of the project portfolio:

Issues

Introducing programme management is not easy. Change generates resistance – will the new system be too bureaucratic; will key staff be happy to give up information; will the process be seen as too complex or not sufficiently complex; what are the training implications? There are also issues surrounding the programme management requirements – how tight or loose should the management system be, and how widely and to what depth should it be implemented?

We believe that buy-in to the introduction of programme management systems starts at the top and board level support is needed. Senior management, in our opinion, need to understand the costs and benefits of programme management before designing a programme management system. Research conducted by Z/Yen’s team, “Vision into Action: A Study of Corporate Culture”, Journal of Strategic Change, Volume 1, pages 189-201, John Wiley & Sons (1992), identified ten key themes followed by most successful change programmes, which we believe apply equally to programme management:

- Direction from the top.

- Emphasis on incremental change.

- The crisis point as a trigger.

- Culture change as an act of faith.

- Involvement of staff.

- Visibility of leaders.

- Living with change.

- The management development spiral.

- Alignment of terms and conditions.

- Decentralization and delayering.

A typical client might follow some or all of the following six stages:

- A clear specification of the problem, the objectives of a programme management project, the benefits, the costs, the risks and a suggested project plan for programme management, supported by facts and figures on things such as project overruns, scope changes, benefit losses and costs;

- Development of a management information structure for programme management, i.e. the information a programme management structure should provide in order to help management control their myriad of projects;

- Development of the ‘light’ programme management system, perhaps using Z/Yen’s Z/ENITH management system as a basic, starter pack. A light system can be developed over time. The light system then becomes the core control mechanism for project managers throughout the organisation;

- Development of an initial scorecard, project appraisal process and portfolio management system;

- Training and roll-out, almost certainly preceded by a pilot;

- Enforcement and learning – programme management and project management need strong, top-down leadership before they become part of the culture.

Next Steps

The first stage, Specification, is more of a ‘study’ than development or training, but this first stage is crucial for convincing decision makers of the need and benefit of programme management. Without a clear specification of the problem and suggested solution, a lot of work could be done on developing a programme management system that would be rejected by the organisation’s project managers. Z/Yen would be pleased to discuss how to develop appropriate programme management for any organisation.